Design Credit

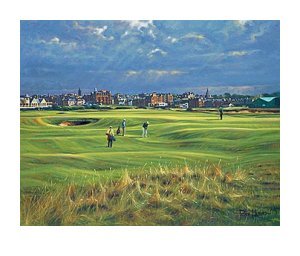

This is the 7th at ballantrae in it's original form. Ballantrae: routed by Doug, designed by me, two holes new holes by Cam Tyers.

There have always been a lot of questions about design credit. It is an issue for the associates within a firm. It is a much bigger issue when two architects go there separate ways. It is an issue after a major renovation. I thought today I would wade into the debate about design credit and provide some examples.

Let’s start with the idea of renovation and restoration. In any restoration, the restoring architect should never get credit for the work. The original architect should be the only one listed. I personally think that an architect must add at least a couple of holes before there is any credit given. A bunker job or rebuilding a few greens is not enough. Where it gets grey is rebuilding all 18 greens, and personally I think it would take all 18 greens to give design credit.

I have always believed that whoever routed the golf course should be given design credit for the course. Routing is so essential that even just a routing is enough to be listed as the designer or co-designer. I think if another architect picks up the rest of the project, they should get credit as a co-designer. On the other hand, I think if the architect is in the field on behalf of the firm, but did not have a hand in the conception of the holes; they probably should not get credit.

I think if an associate has laid out the course and taken it to completion on behalf of a company they should get design credit. Hurdzan Fry is a firm that handles this well, where they name themselves as the architects of record and then name the individual designer. I always thought this is a wonderful way of giving credit where credit is due. As a researcher and historian, I always want to find the architect who actually should be given credit rather than just listing the most popular architect as the architect of record.

One of the new nine holes at Nobleton Lakes

So why does this matter? Well to some it does not, whereas to others it does matter. Sometimes the credit issue can be the wedge that drives a company apart. I like to receive the credit for the work I do, whether it was for Carrick Design, or now on my own. I’m proud of what I do and I think it is important that people know what I have done so I get the proper consideration for future projects. Sometimes the desire for an associate to receive full credit leads to uncomfortable relationships between the principle of a firm and the associate. Many principles want to take all the credit even when there role was largely administrative because of the attention they receive (to make this clear - this was never the case at Carrick). Also, many seem to feel it is important not to recognize the associates to keep them for creating a reputation that may eventually exceed the principle.

When this tenuous relationship breaks down, we are left with the battles over credit after the associate leaves particularly if they did all the work. Doug and I seem to have done OK on this end, unfortunately it's the clients who usually list only Doug. To clear any misconception, I would like to point out that the Ontario Golf News piece suggested I may have been the lead on certain projects, whereas the reality is that I was at best co-designer on some but most often the man in the field. Doug is listed as the designer of record on all new projects and that is fine with me. At this point I don't want recognition for any of them, I just want it known that I got them built and that is where my experience comes from. It is the renovation and restoration work where credit is most important to me.